According to its mission statement, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an agency of the U.S. government, “increases the health security of our nation.”

It does so primarily in two ways: researching diseases and their cures, and informing the public about its findings. For example, you might remember CDC’s role in warning citizens about the zika virus in 2015.

It does so primarily in two ways: researching diseases and their cures, and informing the public about its findings. For example, you might remember CDC’s role in warning citizens about the zika virus in 2015.

A few words might be missing

Soon, however, when you get information from CDC, a few words might be missing. Reportedly, senior officials within the Department of Health and Human Services recently decreed that CDC and other HHS agencies are forbidden from using 7 words in their official budget documents.

(This is a developing story. On Sunday, CDC Director Brenda Fitzgerald called the report about the 7 words “a complete mischaracterization of discussions regarding the budget formulation process.” The word mischaracterization leaves wiggle room: it’s reasonable to assume that there was discussion about avoiding certain words — even if it wasn’t an all-out ban.)

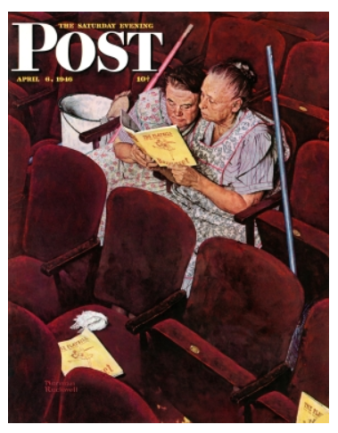

Credit: Scott Smith (@stampergr) on Twitter

Here are the 7 forbidden words:

- vulnerable

- entitlement

- diversity

- transgender

- fetus

- evidence-based

- science-based

What does it mean when words become non-words? As anyone who’s read George Orwell’s 1984 knows, it’s an attempt by those in power to impose control.

They know something I’ve known throughout my writing career: words matter. A lot.

By changing the words in the conversation, do the people in charge at HHS think they can change reality? No. I don’t believe they’re that foolish. Not all of them anyway.

They can’t change reality, but they can change the way in which reality is discussed. If they change the terms of the discussion, they can influence the way people think.

When nothing can be described as evidence-based or science-based, there’s no longer a need to question a finding that’s unsupported by evidence.

When transgender is stripped from the vocabulary, they can more easily dismiss the health needs of thousands of our fellow ci.tizens.

When they stop saying vulnerable, it’s easier for them to overlook human beings who are vulnerable and who need help.

The Florida tides

It brings to mind what happened in Florida a few years ago. The state’s Department of Environmental Protection ordered its staff not to use the terms climate change and global warming in any official communications, emails, or reports.

This despite the fact that, according to a New York Times article, “when many cities in Florida flood, which can occur even without rainfall during the highest tides, fish swim in the streets and people wade to their cars.”

But the nabobs in the Department of Environmental Protection, even as the bottoms of their trousers get soaked, need not trouble themselves with the thought that this is anything more than a random natural phenomenon.

What can we do?

There’s a lot at stake here. Although it’s tempting to smirk and roll our eyes, we mustn’t dismiss this as mere bureaucratic foolery. Instead, we need to call it out for what it is: an attempt by those in power to impose control.

Be wary of gaslighting — of any attempt to change the way reality is perceived. Don’t let Why don’t we talk about x any more? turn into X never happened. All of us share a duty to know the truth and hold fast to it.

Finally, even if HHS won’t use those words, by golly we can use them. And we should. Question what this government tells you — and don’t be afraid to answer back, What about the vulnerable ones? What scientific evidence do you have for this?

Never let them forget that words matter.

Baseball begins in the spring, the season of new life.

Baseball begins in the spring, the season of new life. In football the specialist comes in to kick.

In football the specialist comes in to kick.